The Regatta of San Ranieri

The Regatta of San Ranieri is an exciting race that pits neighbor against neighbor in a hotly contested rowing competition while also being a reconstruction of the historical Battle of Lepanto. With all that’s at stake, it’s no wonder the people of Pisa turn out by the thousands to join the pre-race parade and participate in the festivities.

History of the Race

The history of the race begins in 1292 when it was held to honor the assumption of the Virgin. At the time it was probably a footrace with a palio and livestock as a prize. When Pisa was occupied by Florence in 1405, the games became sporadic. We know they were held once in 1440 in the form of a regatta to celebrate the victory of Florence over the Milanese. It was held again in 1494, but it disappeared from history when the Florentines took control of Pisa in 1509. It was until 1635 that the games were resumed in the form of a regatta.

Though originally meant to honor the assumption of the Virgin, the purpose of the race was changed when it resumed in 1635. San Ranieri had become patron saint of the city just a few years earlier in 1632, so the event was changed to honor him on his date of observance, June 17.

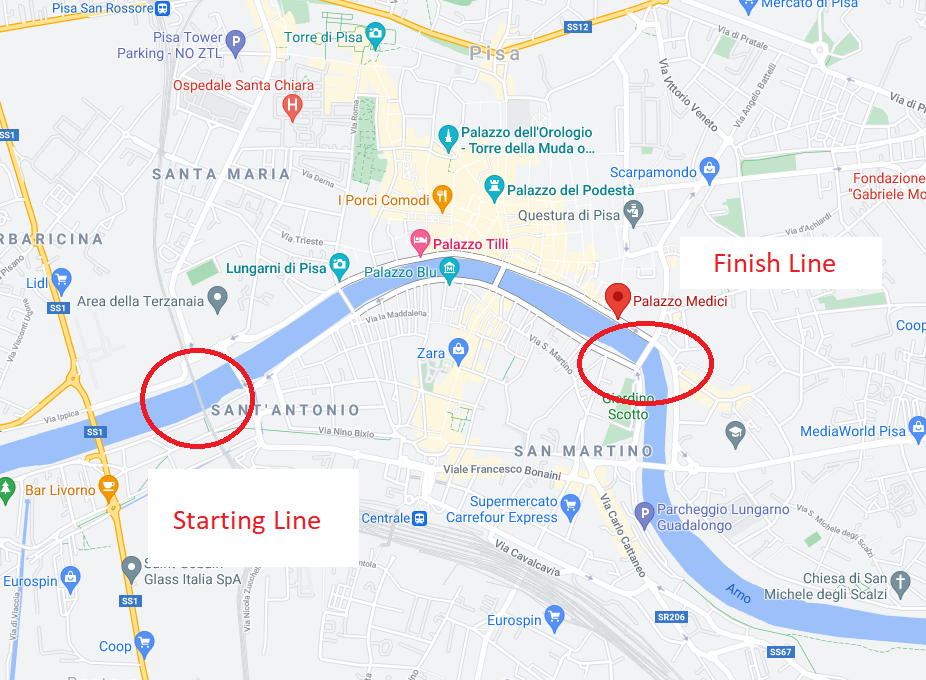

Since it was restarted in 1635, the race has always been held on this part of the Arno river. It was adjusted slightly in 1737 when the finish line was moved to be in front of the Medici Palace so the Duke of Montelimar, who was living in the palace at the time, could see better. This has been the finish line ever since.

Why a Regatta?

When resumed the games were held as a regatta to honor the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. At the time the Ottoman Empire had control of the eastern Mediterranean Sea, which the Catholic Church was unhappy about. Pope Pius V gathered together leaders from the Iberian Peninsula and the Italian Peninsula to form the Holy League, whose purpose was to defeat the Ottoman Empire.

By John Fincham

On the 7th of October, 1571, the Ottoman fleet was sailing west when they encountered the Christian fleet sailing east in the Mediteranean. Thus ensued the largest naval battle of the time, involving more than 400 ships. The battle is described by historians as an “infantry battle on floating platforms”. Though some of the ships had mounted guns and artillery, most did not and the soldiers fought hand-to-hand.

This was the last major battle fought with oared boats since the Age of Sails was beginning and Galleons were becoming more popular. This battle was the turning point that stopped the Ottoman Empire expansion into the westerrn Mediteranean.

History of the name Palio

Many races today are called Palio, and the name has an interesting history. Long ago the word “palio” actually referred to the banners used to honor kings and emperors. The winners of races and other contests would receive what was called a “palio” of silk, wool, or velvet, which were highly prized at the time. Over the years the phrase “running to win the palio” became “running the palio” so that today the word refers to the race itself, not the prize.

In Pisa, the winner of the Palio would also get some livestock. Cows, sheep, and pigs were common for the winners, but the loser would get only a “i paperi”, or pair of ducks. Today that has changed to a pair of geese, but last place is still said to get “i paperi”.

Four Quarters of Pisa

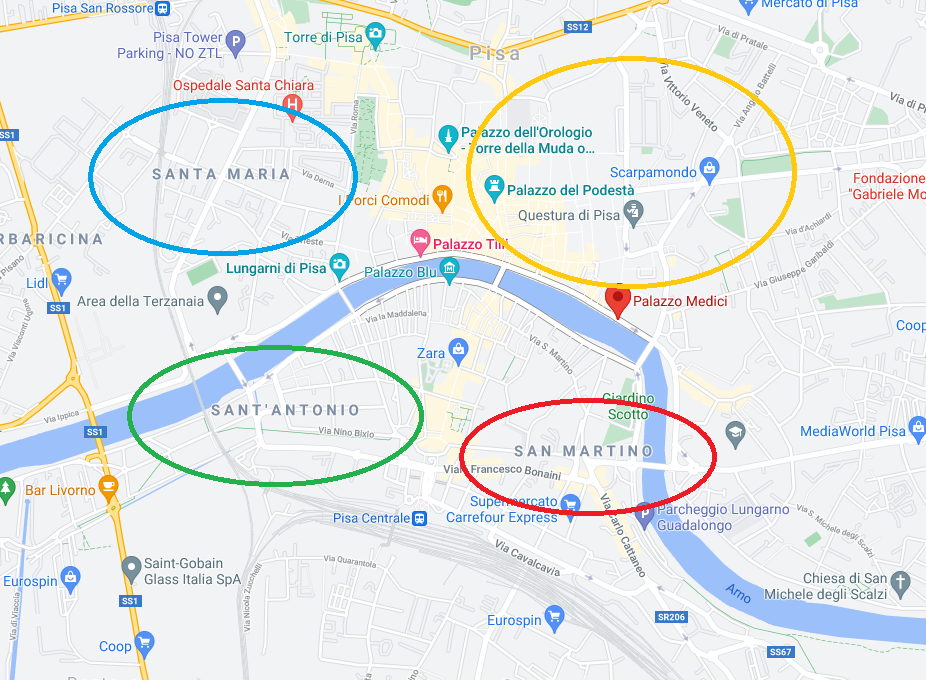

The modern day race is among 4 boats that represent the four quarters of the city of Pisa. The blue boat is for Santa Maria, red is for San Martino, yellow is San Francesco (the neighborhood name is not shown the map, but is in the yellow circle), and green is Sant’Antonio. The local residents turn out in the thousands to cheer on their neighborhood.

The Boats

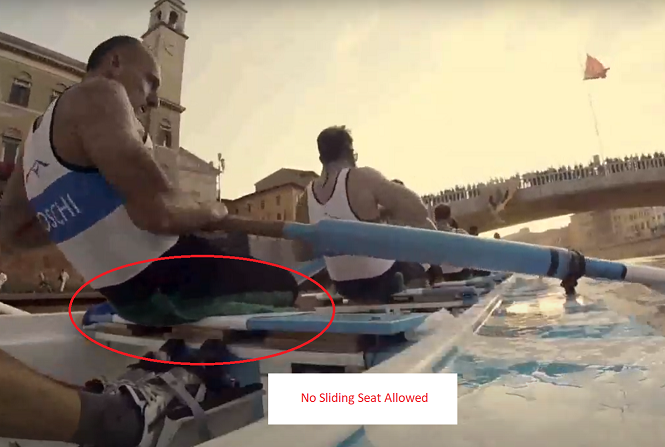

The regatta uses the same boats each year, which are built in the style of the frigates that participated in the original Battle of Lepanto. These boats are prized possessions of the city, and are held by the official race committee throughout the year, only releasing them to the participating neighborhoods 50 days before the race so the rowers can train. No modern attachments are allowed on the boats, most significantly no sliding seats for the rowers which can make their task much easier.

Each boat is crewed by 10 people, all of whom must have been born in Pisa and have lived there for the previous 3 years. The crew consists of 8 rowers, the helmsman (called the timoniere), and the climber (called the montatore).

The Rules

All the boats line up at the Ponte della Ferrovia and when the cannon goes off they all race 1500 meters up river to a boat anchored off the Ponte della Fortezza, near the Palazzo Medici, in effect attacking the boat. When the competitors reach the finish line they send their “montatore”, the fastest climber in their neighborhood, up the mast to capture the flag of the “invading” boat. This mimics how the original Battle of Lepanto happened, where a captured boat would have its flag taken down. If you are interested in the history, the original captured Turkish flag can still be seen at the Church dei Cavalieri.

The boats are assigned a starting position on the river at random, left to right. Though they must each stay in their lane for the first 433 meters (marked by buoys), once past this point they are in “open water” and can head directly to the finish line, potentially cutting off other boats. Cutting in front of another boat can only be done when the helmsman of the lead boat is in front of the bow of the other boat.

The competitiveness of the race has resulted in several disqualifications over the years as boats cut in front of each other too early, and occasionally spear each other with oars.

The Finish Line

At the finish line of the race, there is another boat at anchor that represents the Turkish “enemy” boat that is being attacked. The enemy boat has a 30 foot mast held down by 4 ropes, and with 3 flags at the top for the four competitors.

As each boat approaches the enemy boat, their montatore jumps out and onto the enemy boat, then climbs any one of the ropes to the top of the mast. Quite often there are several montatores climbing ropes at the same time, so the excitement can reach critical levels.

First place goes to the montatore that captures the blue flag, second place is the white flag, and third place is the red flag. The montatore last to arrive is awarded “i paperi”, or “the ducks”. After capturing the blue flag of victory, the winning team gets to take the trophy home to their quarter of the city for display until the next year.

Here is a good video to give you an idea of what the race is like.

Winner History

In the last 20 years, Santa Maria has won 10 of the races and San Martino another 8, with San Francisco winning 2 and Sant’Antonio winning zero. Those numbers are deceiving, though. Over all the results since 1934, Sant’Antonio is nearly tied with Santa Maria for the most victories so they are hungry to get the blue flag.

Logistics

Unfortunately, the race has been canceled in 2020 and 2021 due to Covid. We are hoping for a return in 2022.

The race is a fun day for the family, with a parade along the Arno river through the streets of Pisa before the start. Due to the heat typical in Italy in June, the race start time was moved to 6PM to provide a more pleasant experience.

The race starts at a train crossing bridge that has no name in Google Maps, but is just west of Ponte della Cittadella. It then travels 1500 meters up river to the Ponte della Fortezza, which is right in front of the Palazzo Medici.

Due to the people in town for this event and others the same weekend, I would not advise driving into town. There are 2 train stations in Pisa and both are walking distance to the event. With the late start of the race, you can spend the day visiting the other attractions the city has to offer, then wind your way to the river for the evening.

The event is free and easy to find room along the river to watch the boats go by. There will be crowds at the finish line so if you want a good view arrive early and stake out a spot at the rivers edge.